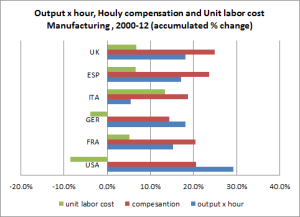

This week Il Diario di due economisti (today on Il Foglio, pag. 2, and tomorrow here) is about the German Model. For German Model is meant the way Germany made the structural reforms in the first half of last decade, which changed its institutions and above all labor market and industrial relations.  The German Model is a mix of the German View – the fallacious idea that fiscal consolidation may be expansionary (or at least cyclically- neutral) in any case and circumstance – and the Social Market Economy (Soziale Marktwirtschaft) principles. These principles call for a corporatist solution of social conflict (once it would been called “class-struggle”), a way to make compatible or harmonize opposing interests through the active intervention of government, in the aim to minimize the negative effects of creative destruction. Maybe (Neo)Corporatism had some merits in building the post II World War welfare state in Continental Europe, but is affected by a big weakness: it is subject to a status-quo-bias that prevents inclusion, hinders innovation, curbs dynamism. To understand what the practical implications of this German Model could be, I propose here some evidence that is different from the one I used in the column for Il Foglio. In the Diario-column I mentioned data for labor productivity, wages and unit labor cost for the whole economy in a 5-countries sample. Now, for the same variables and for six countries I show the evidence for the manufacturing sector only. For the manufacturing aggregate, the concept of labor productivity is sounder than for the overall economy (raw data come from ILC program of BLS and CB ). Labor productivity is proxied now by (real ) output per hour (worked) in manufacturing (instead of real Gdp x hour), wage is hourly nominal compensation of all employed persons (employees and self-employed workers) in manufacturing, and unit labor cost (the cost of labor input needed to produce one unit of output) is roughly the difference between the respective rate of change of hourly compensation and hourly productivity. All variables are expressed in national currency and thus data on unit labor cost, which is a measure of competitiveness, does not take into account the effect of exchange rates (that in the period considered here had worsened the competitiveness performance of European country given the Euro appreciation). I first computed the average annual compound rate of change for these variables, and then obtained the accumulated change that is used for the graph. The first graph is relative to the period 2000-2012, the second to the pre-crisis period 2000-2007. For our purposes, what these data show is that the better performance of Germany in terms of competitiveness among the five European countries is the result of a productivity improvements-wage moderation mix. Germany is not a miracle in terms of productivity gains: its performance (+ 18.2%) is lower than that of Usa, and comparable with that of United Kingdom, Spain and France. Here Italy is clearly the outlier (productivity disease is the basic problem of Italy). But where Germany performs excellently is in the wage short dynamics (the lowest of our sample) and this makes it possible that Germany gains competitiveness in respect to the other European countries. But how the Usa experience demonstrates, a good performance in terms of competitiveness (the best in this sample) can be reached even with a different mix. What is truly miraculous of the German Model is the capacity to persuade workers to accept to be paid less, relative to productivity improvements, than in other countries. This is the consequence, coeteris paribus, of the structural reforms of the early 2000. The crucial role of productivity and the need of supply-side policies (structural reforms) to foster potential output, are demonstrated by the case of Spain.

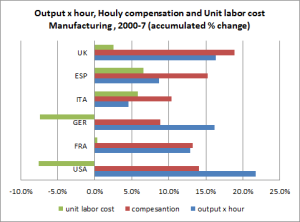

The German Model is a mix of the German View – the fallacious idea that fiscal consolidation may be expansionary (or at least cyclically- neutral) in any case and circumstance – and the Social Market Economy (Soziale Marktwirtschaft) principles. These principles call for a corporatist solution of social conflict (once it would been called “class-struggle”), a way to make compatible or harmonize opposing interests through the active intervention of government, in the aim to minimize the negative effects of creative destruction. Maybe (Neo)Corporatism had some merits in building the post II World War welfare state in Continental Europe, but is affected by a big weakness: it is subject to a status-quo-bias that prevents inclusion, hinders innovation, curbs dynamism. To understand what the practical implications of this German Model could be, I propose here some evidence that is different from the one I used in the column for Il Foglio. In the Diario-column I mentioned data for labor productivity, wages and unit labor cost for the whole economy in a 5-countries sample. Now, for the same variables and for six countries I show the evidence for the manufacturing sector only. For the manufacturing aggregate, the concept of labor productivity is sounder than for the overall economy (raw data come from ILC program of BLS and CB ). Labor productivity is proxied now by (real ) output per hour (worked) in manufacturing (instead of real Gdp x hour), wage is hourly nominal compensation of all employed persons (employees and self-employed workers) in manufacturing, and unit labor cost (the cost of labor input needed to produce one unit of output) is roughly the difference between the respective rate of change of hourly compensation and hourly productivity. All variables are expressed in national currency and thus data on unit labor cost, which is a measure of competitiveness, does not take into account the effect of exchange rates (that in the period considered here had worsened the competitiveness performance of European country given the Euro appreciation). I first computed the average annual compound rate of change for these variables, and then obtained the accumulated change that is used for the graph. The first graph is relative to the period 2000-2012, the second to the pre-crisis period 2000-2007. For our purposes, what these data show is that the better performance of Germany in terms of competitiveness among the five European countries is the result of a productivity improvements-wage moderation mix. Germany is not a miracle in terms of productivity gains: its performance (+ 18.2%) is lower than that of Usa, and comparable with that of United Kingdom, Spain and France. Here Italy is clearly the outlier (productivity disease is the basic problem of Italy). But where Germany performs excellently is in the wage short dynamics (the lowest of our sample) and this makes it possible that Germany gains competitiveness in respect to the other European countries. But how the Usa experience demonstrates, a good performance in terms of competitiveness (the best in this sample) can be reached even with a different mix. What is truly miraculous of the German Model is the capacity to persuade workers to accept to be paid less, relative to productivity improvements, than in other countries. This is the consequence, coeteris paribus, of the structural reforms of the early 2000. The crucial role of productivity and the need of supply-side policies (structural reforms) to foster potential output, are demonstrated by the case of Spain.  How the second graph shows, Spain made a significant adjustment in terms of productivity after the crisis, even by the means of structural reforms, and this made possible an important improvement in competitiveness even in presence of a faster wage dynamics.

How the second graph shows, Spain made a significant adjustment in terms of productivity after the crisis, even by the means of structural reforms, and this made possible an important improvement in competitiveness even in presence of a faster wage dynamics.

Sofia

Il blog di economia